Electronic music for experimental theater, ballet performances and documentaries.

A chat with Roger Baudet.

Described by Swiss press as an “inventive genius marked by total unpredictability,", Roger Baudet’s music has preserved its freshness and spontaneity. Provoking feelings of surprise, anxiety and subjugation, he ends up bewitching you completely through his bizarre non-conformity. The oddity of the sounds is a choice of heterogeneity: the works gathered, although coming from one person, have little to do with each other.

Forming a mosaic that provides a fragmented vision of atmospheres without apparent links, his music multiplies diverse rhythms and combinations, rejecting any principle of hierarchy in the musicality of the moment. The decorative music was composed as the soundtrack for theatre and ballet performances, documentaries, short films and exhibitions of paintings – a context that inevitably shines through the twenty-two pieces. Despite these classical settings, the music had a forward-facing, futuristic cadence – a precursor to the electronic genres that would later become techno or trance. This compilation from the past century is a collage of ornaments made out of sounds; stripped down, yet undoubtedly imbued with sensitivity, with hints of classical training, all suitable for contemplation.

Born on 19th February 1951, in Geneva, Switzerland, Roger Baudet studied piano at the conservatories of Geneva and Lausanne before becoming interested in soundtracks in addition to filmmaking. Passionate about merging sound and image, he found himself pursuing a profession as an animator. An interest in music, images, people; the vitality of youth and life led him to a teaching position at the animation centre of Nyon from 1977 to 1981. However, this was interrupted when a health issue pushed him to live a more solitary life. While composing soundtracks for films, plays, dance and ballet shows, Roger Baudet decided to burn his sonorous and solitary reveries onto magnetic tape, presenting his music in the form of minuets as well as varied compositions. From then on, the idea to set up an electroacoustic music studio in Lausanne was born, where his mixing board, synthesizers and drum machines resulted in the genesis of a universe of sounds with disturbing, ironic and tender melodies without taboos or borders.

In his studio, Roger Baudet looks like he is surrounded by giant metal and plastic jaws, with the keys of the machinery as the teeth. As a composer, he sought after a machine that did not slavishly imitate the sounds of traditional instruments, but instead acted as a springboard that allowed him to go beyond conventional tropes. For this purpose, he opted to work with computers, synthesizers, drum machines and magnetic tape loops – technology that attracted him for its efficacy in translating his ideas into productions. It was important to distinguish between the limitations and possibilities of acoustic and electronic instruments. He enjoyed the familiarity of everyday sounds, but only to reshape and transform them through an altered context, thus enabling an exploration of sonic boundaries, as can be heard in ‘Mal à l'aise’ (1982), where he sampled his children’s voices. He readily admits that he finds beauty and wonder in such machines since they are untamed and its users are captives of its infinite possibilities. The palette arrives in the hand, but the painting needs to be done.

Driven by action, Roger Baudet’s music is simultaneously guided by his insatiable improvisations, a mode of working that is encapsulated by the charm of his dishevelled and bright personality. The cyclical, floating rhythms ebb and flow – a sound in perpetual motion – that moves with organic recurrence. Ambient music at its core may calm, but it can also be listened to in a thousand ways; your attention becoming fluid as the sounds that flow from his machines. The melodies capture out-of-the-sky moods; the interlacing notes hypnotize you, sensually binding together to form a sumptuous harmony. The themes do not obey any convention or stable form; the associative stream of images and emotions are conjured as if by some strange alchemy.

The need for originality and the desire to combine audio with visual art pushed Roger Baudet to produce his own shows. Compositions such as ‘Sérénade d’un autre monde’ (1978), ‘Légère Complainte’ (1982), ‘Complainte à Deux’ (1982) and ‘Where are you’ (1986), evolved around experimental ballet dances that he would score live. In general, the demand for this type of music back in the early 1980s was not immensely high, as such avant-garde performances were uncommon as was familiarity with the music technology. The first people to have done this with popular success was choreographer Maurice Béjart and composer Pierre Henry and Michel Colombier (both incharge of the electroacoustique sounds and instrumentals, respectively), with their collaborative ballet piece Messe pour le temps présent (1967). They successfully combined the extreme contrast between pop, experimental, classical dance to create an amalgamation of movement and sound, pioneering a new art form.

Visual art has always had a place in Roger Baudet’s approach to music. In the beginning of his career for example, he would host art exhibitions with his friend Thierry Bugnion, where he would generate soundtracks to further illustrate and give life to the paintings. Although this exhibition was successful and highly regarded by local press,

Roger Baudet’s breakthrough production was for the ballet piece Comme une Distance (1983). Performed entirely live, with the use of reel to reel tape recorders to serve as the rhythm section, the influence for this soundtrack came from the very aggressive “Berlin music" of that time. Choreographer Dominique Genton's instructions were clear: “I want hyper-rhythmic music, but without the use of any actual drums!"

At the time, the combination of these tracks with a performance was a big hit that got all of the French-speaking part of Switzerland talking. Drum machine-style sequences were emulated through tape delay and echo on percussive recordings that were created through improvised tools – including Roger’s own voice. His beat-driven snarls and breathing repeating and disintegrating as the tape loops overdubbed each other. Contact microphones were also placed under the stage where the ballerinas danced. Each time they would jump and land, the sounds were captured and then pitched down with the aid of a pitch shifter, creating cannon-like explosions that emulated a kick drum. To achieve an echo chamber, reel-to-reel tape recorders of about 5 metres were placed facing away from each other. The echo would be generated from the reverberated sound of the tape loop going from tape recorder to the other. People would not understand that the music they were hearing was made live in front of them, and not from a recording.

“You can see that (see picture below) the curtain behind me is actually a jeep parachute that we got from a military surplus. At the beginning of the performance, the parachute was on the floor – you couldn’t see it. When the bass would hit the parachute would glide over the audience with the help of rope and mechanics, creating a tent over the crowd. Because a short intermission was needed for the dancers and performers to change costumes, I would come out from the orchestra pit and get on stage. The keyboard you see me holding there was connected to other mechanics and every time I would hit a key, the bass sounds I was telling you about would launch. This technique was similar to the function and usage of today's samplers – taking familiar, organic sounds and pushing them further beyond recognition.”

In his early years, Roger Baudet favoured this style of musique concrète with tape loops due to the low availability and high prices of synthesizers at the time. The idea of a solo performer playing in a style that shared no connections to rock – then the most popular genre – was very alien and made it at times difficult to attract an audience. His music mainly gained interest from younger audiences, as it held aesthetic educational value and grasped their curiosity. Like-minded people – although very few in number in Swiss Romande in the late 1970s early 1980s – could have access to such leftfield artforms through Gérard Suter’s radio show on Espace 2 (a Swiss-French radio station), called “Démarge”. It was a late night experimental radio program with talk-show-like material in between the songs, where the host and his guests would discuss themes such as science and philosophy. Roger Baudet – among other like-minded musicians – played on that radio program, which allowed leftfield creatives to meet each other.

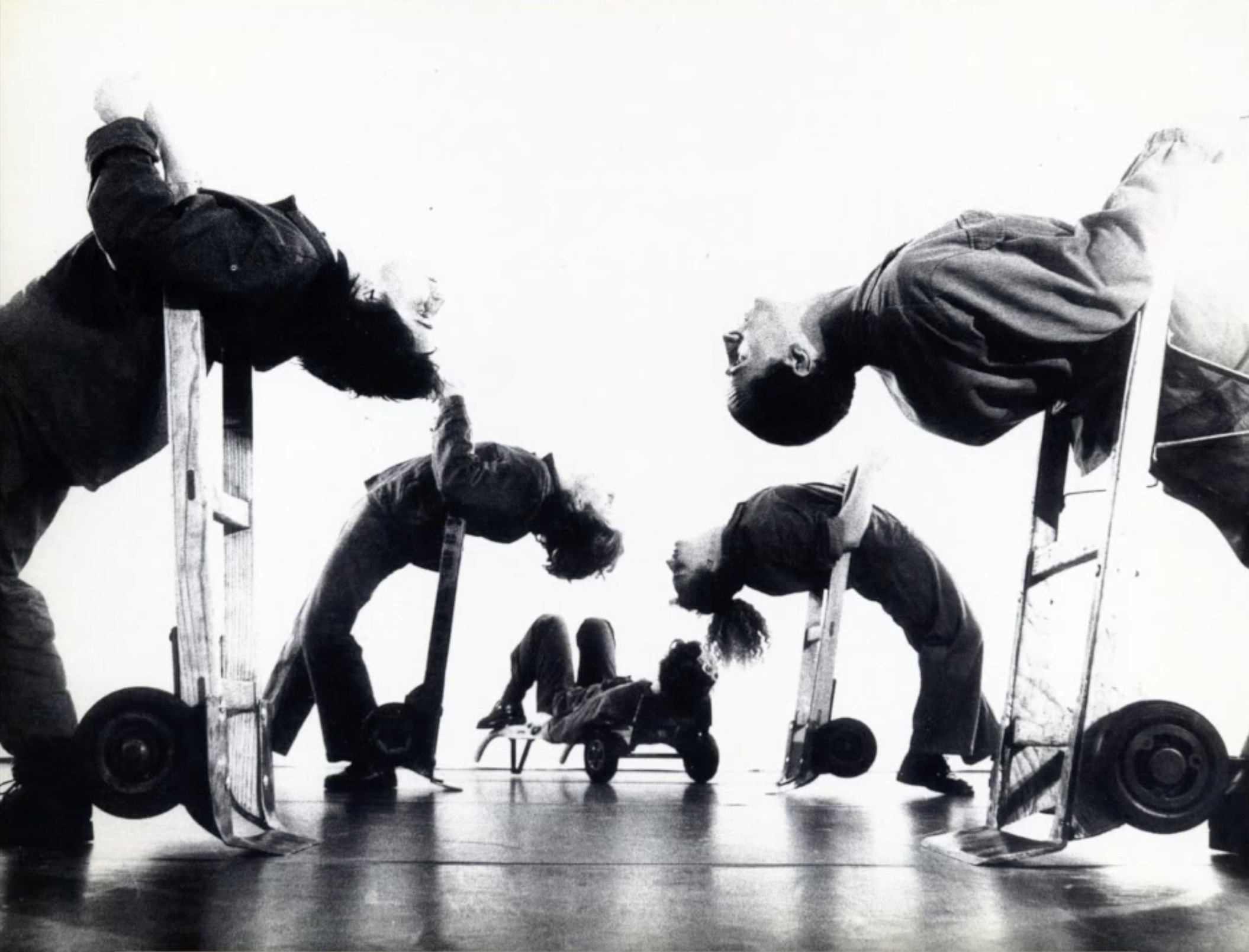

Mov ’in. Performance art concept coordinated by Christian Mattis and soundtracked by Roger Baudet. Lausanne, circa 1989.

“Finding a venue to give a concert under my relatively unknown name was at times very difficult. When trying to achieve something like what [Jean-Michel] Jarre did with the use of lasers and projectors, the issue of finances became a problem. To reduce the costs, I had to improvise on a smaller scale using a camera and a slide projector. If you produced your own show, you had to pay the venue, the poster tax, a concert tax, not to mention travel costs, accommodation, and other more or less expensive miscellaneous fees. On top of it all, we were often overlooked by the newspapers. I wrote music for a ballet by Dominique Genton as well as to jingles and callsigns for radio and television. That kind of commercial work was my bread and butter for a long time. Making a living from electronic music in French-speaking Switzerland is not impossible. There are many artists – people like Kashmir, Thierry Fervant or Michel Saugy – who do better than most.”

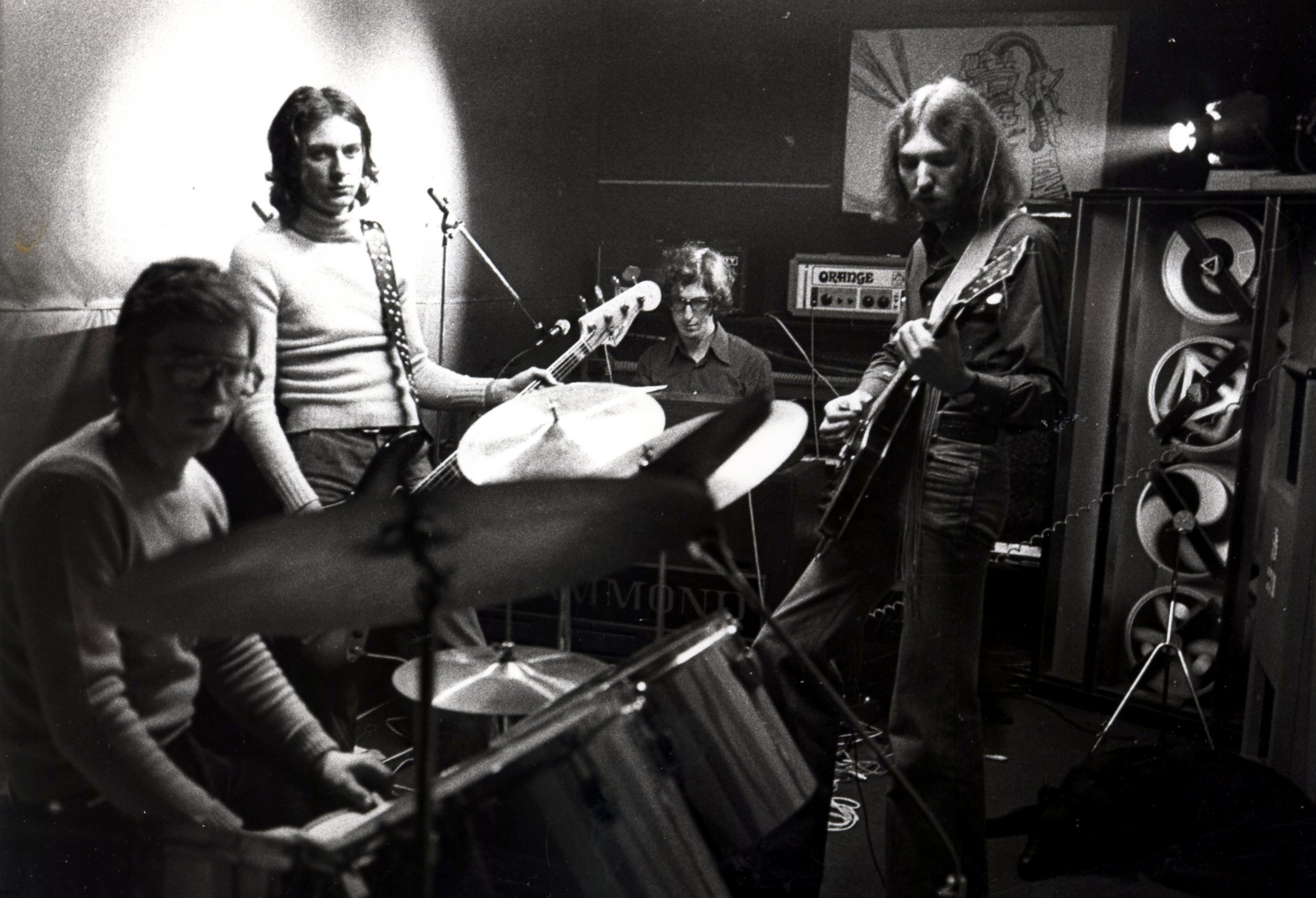

Roger Baudet did not always make music by himself. In 1976, he found a newspaper ad where a band was looking for a keyboardist, which allowed him to experiment with other musicians in a more traditional four-piece format. Saphir was a short lived kraut/prog rock band that lasted only three months. They recorded one self-titled demo - ‘Saphir’. Roger Baudet left the band due to creative differences, albeit remaining amicable, as he wanted to pursue his work in a more solitary fashion. “I don’t think they did much after that. It was actually quite interesting that you (Dee Dee’s Picks) contacted me to release that song because I really thought nobody would have any interest in it, especially decades later. The surprise was shared, if not enthused by the other members when I asked for their permission because they have not done anything music-related since.”

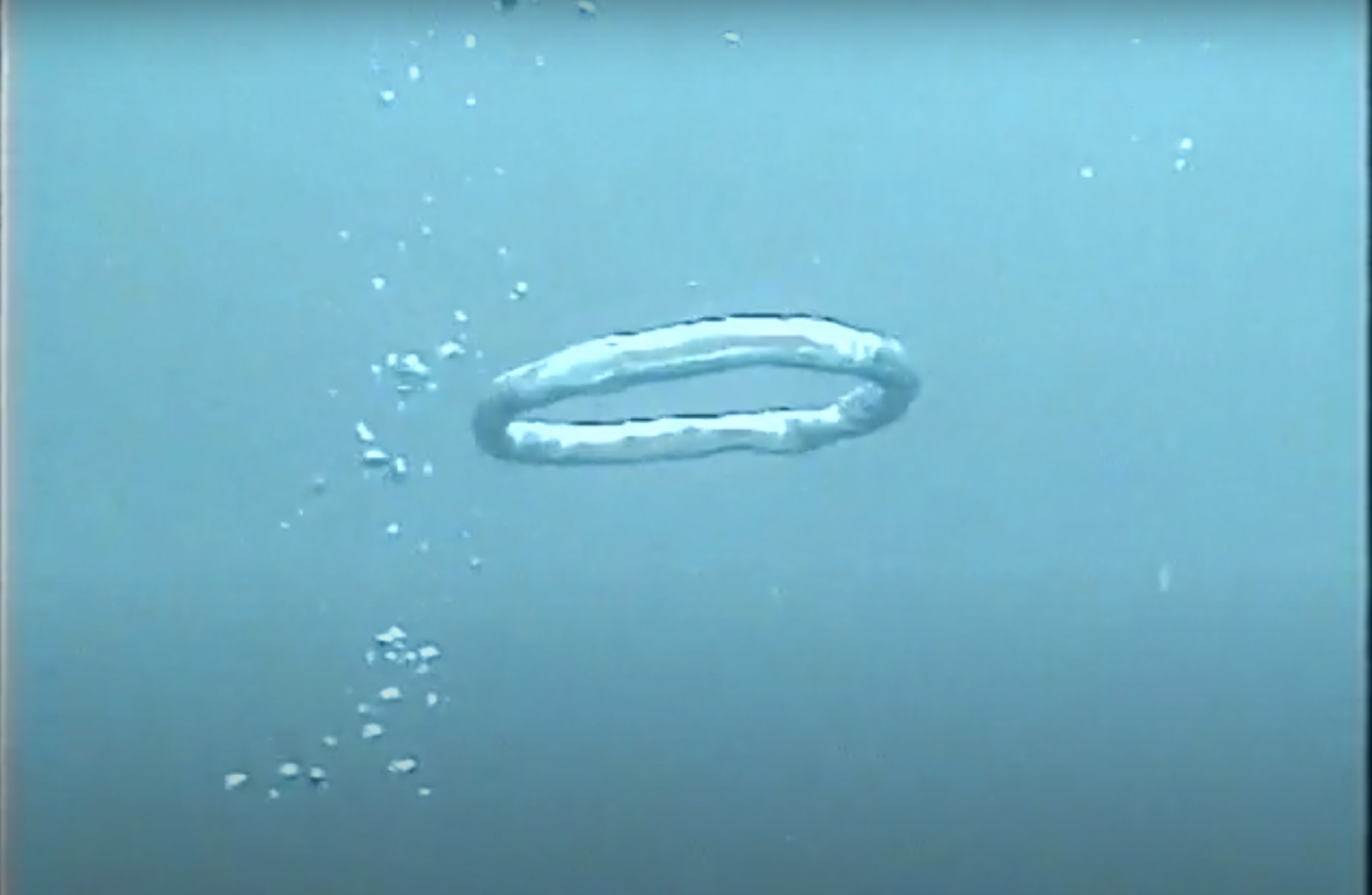

These experimental solo projects went back and forth for a few years, as it was difficult to put a label on such music and to therefore gain interest from both listeners and collaborators. “I remember when I was finally able to afford my first synthesizer, a Minimoog. It took me give or take a year and a half to understand what was going on, as there was little to no information. Back then, there were no internet forums for figuring out how to program such machinery.” One of the first people to become interested in Roger Baudet’s works were choreographers and theatres as they were familiar with Roger Baudet’s work that he had done at the time, such as Lausannoise theatre producer Jacques Gardel. It was only a few years later – when Roger Baudet started to become more known in Switzerland – that he had access to higher budget studio equipment. The use of synthesizers was therefore more present in his soundtracking endeavours. “Scoring soundtracks for deep-sea exploration and nature documentaries for programs like ‘Adrenaline’ on the RTS [Swiss radio and television broadcasting company] or ‘Ushuaia’ on TF1 [French television broadcasting company] really gave me the opportunity to explore different soundscapes.”

Ceremonial is one of his last soundtracks that Roger Baudet did for ballet. The year was 1991, when the technology for sampling had evolved drastically – sound quality, ease of use and technological accessibility had all improved exponentially. Ceremonial was a project where the sounds used conveyed strength, power and turbulence.

“I took a sudden interest in music originating from Africa, where I wanted to incorporate it more in my productions. People found this piece quite impactful, and perhaps even a little too ahead of its time. Compared to the new age scene that was starting to emerge from Switzerland, people like Deep Forest did something along those lines but more down tempo. Ceremonial was something much more energetic and intense. Although the spectacle aspect was successful, nobody ever really took an interest in issuing Ceremonial. Until now, I suppose. The soundtrack was done almost entirely with computers, with sample banks that I derived from CDs at the UNIL [University of Lausanne] sound library and then recorded on my analogue eight-track. The project needed to sound somewhat alien and aggressive – to the European audiences anyways. The idea of using sample packs labelled ‘African Tribal Chants’ seemed appropriate for that, especially after further audio processing of the samples. I thought of merging these elements with contemporary electronica to convey an unfamiliar scenery and soundscape with the use of languages and sounds that were foreign to European audiences. A fusion of these two worlds. People did not understand the concept back then, but you should have seen the audience rise up and clap at the end. It was grandiose, let me tell you that.”